innovation

Innovation and invention by nature are creative processes. People involved in bringing creative processes to fruition possess an ambiguous innate talent, for those not familiar with the work. A divinity of inspiration or a flash of insight or genius while engaged in other pursuits is how the process is often described. Is this an absolute truth or are there other avenues to invention for the rest of us?

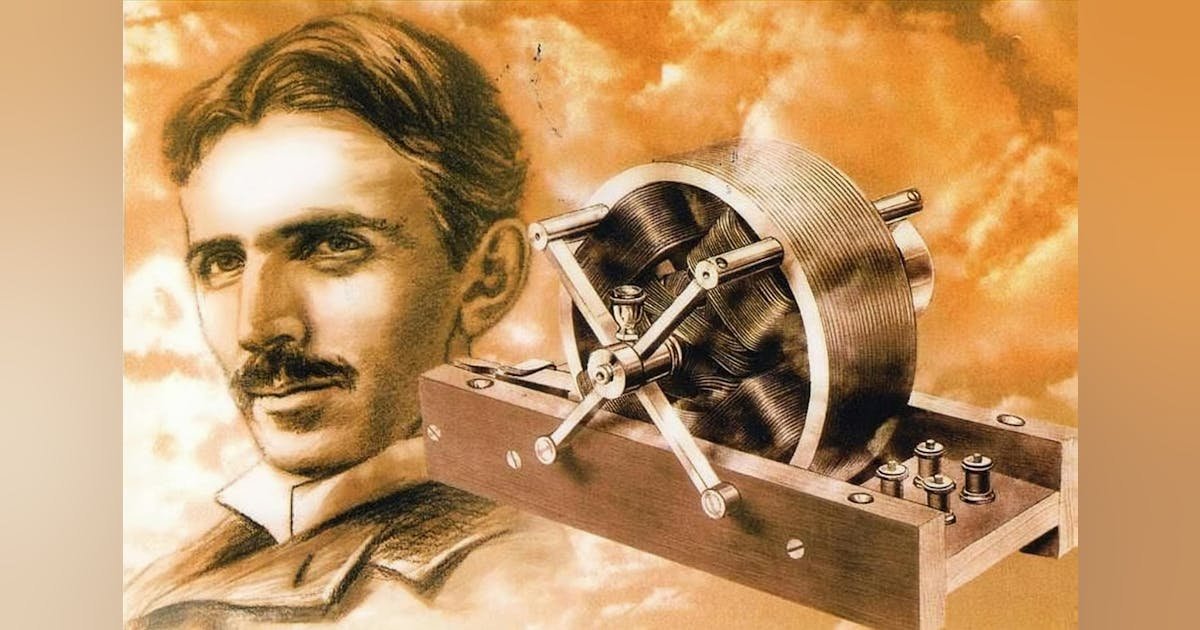

Nikola Tesla, the great Serbian-American inventor, recalls one of his many seminal inventions, the AC motor, with a similar mystic narrative: “Like a flash of lightning and in an instant the truth was revealed. I drew with a stick on the sand the diagrams of my motor. A thousand secrets of nature which I might have stumbled upon accidentally I would have given for that one which I had wrestled from her against all odds and at the peril of my existence.”1

These revelations of how the creative invention process works shroud the fact that invention is largely work for most, while at the same time being a work that requires creativeness, insightfulness, and discipline.

The exception is not the rule relative to invention. This representation of the origin or process of invention—of a genius or heroic lone inventor—is held in regard due to its reinforcement of the American cultural precept that individualism is at the root of most success. This was termed as the “transcendentalism” approach/theory by innovation researcher Abbott P. Usher in his highly cited study2 in 1929. He characterized the invention process as the outcome of one of three approaches: transcendentalism, mechanistic process, and cumulative synthesis.

Let’s look at each briefly and draw some working conclusions to guide us to structured innovation processes. Is this even possible? Or is structured innovation an oxymoron?

The transcendentalism approach attributes invention to the genius of the rare individual who recognizes something not perceptible to even one “skilled in the art” of invention.

The mechanistic process approach footnotes the inventor in the process of invention. Invention in a mechanistic view is driven by historical tension, a temporal crescendo of events and necessity being the driving forces behind invention and new innovation.

Usher rejected these explanations as not supported historically and not considering temporal discontinuities within the invention process that are filled by individuals with “acts of insight.” He proposed a third theory called the cumulative synthesis approach. It asserts that invention and innovation are the historic accumulation of information, needs, and other technologies intersecting in time with the individual whose informed sensibility allows for exceptional acts of insight that enable the creation of a new invention and subsequent market-directed innovation.

The conclusion drawn here is that the cumulative synthesis approach best fits the author’s experience as an inventor and, not uncoincidentally, is supported by numerous theses and studies authored since Usher’s original work. But the transcendentalist approach can be supported historically. Individuals like Einstein, Tesla, Fuller, and Jobs seem to bear this out. The mechanistic view requires little exceptionalism of the individual or organization and has little or no resonance with critically studied historical innovations in literature or this inventor’s experience.

Invention as a structured process

The overview of academic theories of invention is that to be a successful inventor, one is mad brilliant or is someone that who works at it. Discussion of the second approach is more beneficial for most. The brilliant can stop reading here with the understanding that invention for them is a highly individual and even a mystic journey. Personally, I like to characterize this second approach as more of a stonecutter.