In an advance for organic infrared photodiodes, researchers at the University of Turku in Finland recently engineered strong exciton-photon coupling to create a device with an exceptionally narrow detection band and high responsivity—without separate filters.

The team’s organic infrared photodiode is ultrafast and its measured responsivity is competitive with leading organic approaches.

“I’ve always been fascinated by how much information light carries, especially within the infrared,” says Ahmed Gaber Abdelmagid, a doctoral researcher at the time of the work and now a postdoctoral scientist at the University of Cologne in Germany. “In my earlier work with shortwave-infrared (SWIR) detectors, I saw how light can reveal patterns that are invisible to the eye. Organic semiconductors are lightweight, flexible, and easy to process from solution, but achieving highly selective, narrowband infrared detection without bulky structures remains difficult. We wanted to rethink the problem: What if the photodiode itself could act as its own optical filter?”

This motivated the team to explore strong light–matter coupling, in which photons and electronic excitations merge into new hybrid states. And it led to a new way to engineer the detector’s absorption fundamentally, instead of continuing to add more layers.

Selectively absorb a narrow band within the infrared

The key concept behind the team’s organic infrared photodiode is strong coupling between an organic semiconductor and an optical microcavity. “When the semiconductor’s absorption aligns with the cavity’s resonance, they interact so intensely that they form new hybrid quasiparticles—polaritons—that combine the properties of both light and matter,” says Abdelmagid. “These polaritons exhibit sharp energy features inherited from their photonic component and angle-stable optical responses inherited from their material component. We harnessed these characteristics to create a photodiode that selectively absorbs a narrow band within the infrared.”

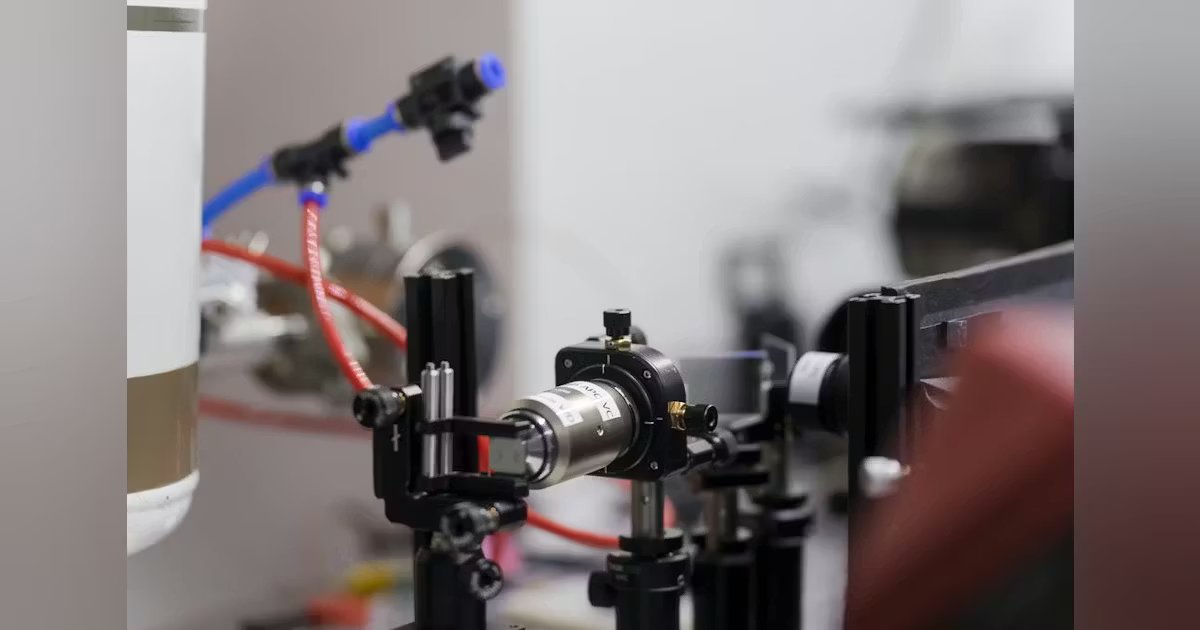

How does the team’s method work? “We place an infrared-absorbing organic layer between two reflective electrodes to form a tiny optical cavity,” explains Abdelmagid. “When the cavity is tuned correctly, the semiconductor and the confined light exchange energy faster than they lose it. This creates polariton states, which control where the device absorbs light. The photodiode then converts only these selected wavelengths into electrical current.”

In other words: The device “chooses” a color to detect by reshaping its own optical properties and maintaining the exciton-like spectrum dispersion that’s crucial for large field-of-view applications.

“The real ‘aha!’ of our work was achieving record responsivity that competes with state-of-the-art organic photodiodes, which is something that hasn’t been shown before for polariton-engineered devices,” Abdelmagid says. “Hitting this benchmark was exciting because it proved polaritons can do more than make pretty spectra: They can deliver practical performance and finally push optoelectronics forward after decades of primarily fundamental research.”

In case you’re wondering, their work did involve simulations—coupled harmonic oscillator models to extract Rabi splitting and polariton dispersion.

As far as challenges, the team is now focused on optical confinement vs. losses. “Stronger confinement improves selectivity but increases losses in mirrors/electrodes and within the organic layers, which can cap responsivity,” Abdelmagid says. “We need lower-loss cavities and better electrode stacks, so further optimization is definitely needed.”